From War Crimes to Chaos: 25 Years That Broke Britain.

Unfortunately, there is currently no way back for the UK.

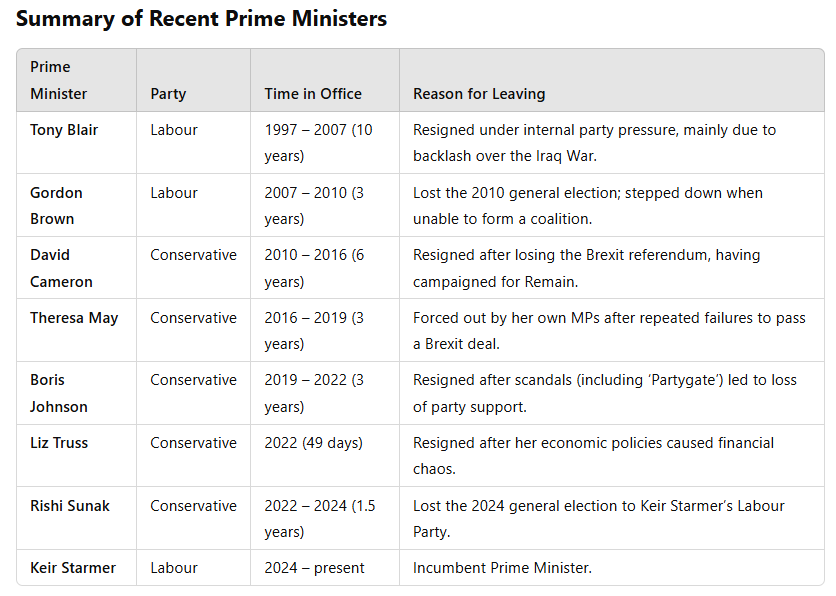

For much of the 20th century, British Prime Ministers either left office through electoral defeat or stepped down at a time of their choosing. However, in the 21st century, resignations under pressure have become far more frequent, signaling a shift in the stability of the country’s leadership. Since Tony Blair’s departure in 2007, five of his successors have been forced out before completing a full term. This raises a fundamental question: has Britain lost its ability to maintain stable leadership?

The Precedent: Tony Blair’s War-Tainted Exit

Tony Blair, who served as Prime Minister from 1997 to 2007, left office under a cloud of controversy, primarily due to his role in the Iraq War. Once hailed as a modernising force within the Labour Party, Blair’s legacy was overshadowed by his unwavering commitment to George W. Bush’s foreign policy and the deeply unpopular invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Though Blair was not forced out in the same way as his successors, his departure was far from smooth. He had become a deeply polarising figure, and internal pressure from within the Labour Party—alongside public outrage—eventually led to his resignation. Many viewed him as a war criminal rather than a statesman, and his exit set the stage for an era in which Prime Ministers were no longer guaranteed uninterrupted leadership.

The Post-Blair Revolving Door

After Blair, Gordon Brown took over but lasted only three years. The 2010 election resulted in a hung parliament, and Brown stepped down when it became clear he could not form a coalition. This marked the beginning of a period where Prime Ministers would increasingly find their positions untenable before a general election could remove them.

David Cameron, who succeeded Brown, initially seemed secure in his leadership, winning an outright majority in 2015. However, his downfall came in 2016 when the Brexit referendum he had called did not go his way. Having campaigned for Remain, he resigned immediately after the Leave vote, unwilling to oversee a policy he did not believe in.

Theresa May then took over. She struggled to unify her party and failed to push through her Brexit deal. By mid-2019, she was forced to resign due to lack of support from her own MPs.

Boris Johnson followed, winning a landslide election victory in December 2019. However, his tenure collapsed under the weight of scandals, including the "Partygate" controversy during the COVID-19 pandemic, which eroded trust even further.

His successor, Liz Truss, had the shortest tenure in British history—just 49 days. Her economic policies triggered financial chaos, and she resigned before she could even establish herself. Rishi Sunak then took over, trying to restore stability, but his time in office was marked by declining party unity and policy stagnation. Like many of his predecessors, he resigned under pressure before an election could finish the job for him.

Is This a Crisis or an Evolution?

The instability at the top is a sign of Britain’s political system becoming dysfunctional. Frequent resignations create uncertainty and make long-term policy planning nearly impossible. The country has seen five Prime Ministers in the space of just seven years (2016-2023), leading to government paralysis and public disillusionment.

On the other hand, one could argue that this represents a more responsive democracy. Unlike in the past, where deeply unpopular leaders like Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair could remain in power despite widespread opposition, today’s Prime Ministers are more accountable to their party and the public.

In recent years, British politics has shown increasing signs of kleptocratic tendencies, where government officials and their associates use political power for personal gain rather than public service. The revolving door between government and private interests—particularly in finance, energy, and healthcare—has allowed many politicians to profit from policies they implement while in office. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed blatant cronyism, with lucrative contracts awarded to companies linked to Conservative Party donors and MPs, often without proper oversight.

Lobbying by former Prime Ministers on behalf of corporate clients, and lawmakers securing lucrative post-government jobs in industries they once regulated highlight how governance has been twisted to serve private enrichment over public interest.

At the heart of this issue is the erosion of accountability. While past political scandals in the UK led to resignations and even prosecutions, today’s leaders often face few real consequences. Boris Johnson's administration, for instance, was plagued by ethical breaches, from misleading Parliament over "Partygate" to reports of ministers spending public funds lavishly with minimal justification. Yet, instead of serious reform, political elites continue to protect their own, relying on short news cycles and public fatigue to escape accountability. As Britain struggles with economic decline, crumbling public services, and worsening inequality, the perception that the country is governed by a self-serving elite is eroding trust in democracy itself.

There are no signs of this trend reversing.

The Rise of ‘Safe Pair of Hands’ Leadership

In an era of political instability, the UK’s ruling elite has increasingly turned to so-called "safe pair of hands" leaders—figures chosen not for their vision or ability to enact meaningful change, but for their loyalty to the establishment and their role in maintaining the status quo. These leaders are often selected through internal party maneuvering rather than popular support, ensuring that power remains concentrated within a narrow elite. Rather than bold reformers, they are risk-averse caretakers whose primary function is to shield the political class from scrutiny while placating financial and corporate interests.

Rishi Sunak’s rise to power exemplifies this trend. Installed as Prime Minister by Conservative MPs without a public vote following Liz Truss’s disastrous tenure, Sunak was presented as a stabilising figure, yet his government remained deeply entrenched in the same patterns of cronyism and economic mismanagement.

Similarly, Keir Starmer, despite branding himself as a break from past Labour leadership, has surrounded himself with advisors from the financial sector and key corporate lobbies, ensuring that his policies pose no real threat to the entrenched power structures. By repeatedly selecting leaders who are beholden to party donors and elite interests, Britain’s political system has become increasingly insulated from genuine democratic accountability, reinforcing public disillusionment and the perception that elections merely serve to rotate one set of establishment-approved managers for another.

Keir Starmer's popularity has been largely driven by public exhaustion with the Conservative Party rather than strong enthusiasm for his leadership. When, not if, he fails to deliver meaningful change—particularly on issues like the cost of living, housing, and NHS reform—disillusionment will set in quickly.

The question is, are there any more cronies left in the closet to bring out, and if there are, how long will they last?

Brilliant read, Thank you !